‘YOU’LL HEAR FROM ME’

Publication date: 9/4/2000

Page: C1

Section: LIFE & LEISURE

Edition: THREE STAR

Byline: MICHAEL LOPEZ, STAFF WRITER

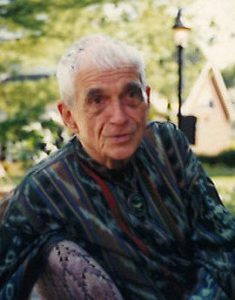

In his 1987 autobiography “To Dwell in Peace,” the Rev. Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit who has spilled his own blood for peace, contemplated the legendary attempt of St. Francis to tame the wolf. A painting Berrigan owned, the allegory of the wolf, with its human eyes still full of animal wariness, taught him a lesson about narrowing the gulf between violence and peace: He must neither be too pessimistic nor too hopeful. This good must be done simply because it is good.

So, at 79, and 20 years after famously splashing blood and hammering on disarmed nuclear warheads, Berrigan resolutely continues his activism, criticizing the presence of ROTC on college campuses, protesting at the maritime museum USS Intrepid, gruffly dismissing this election year as a charade devoid of the important moral questions.

Although his recent work is quieter than his fame as anti-war protester and prisoner, rest assured, “You’ll hear from me,” Berrigan said Wednesday at The College of Saint Rose.

Berrigan’s long resume of anti-war activism is dominated by two prominent protests. As part of the Catonsville Nine, Berrigan in 1968 burned files taken from a Maryland draft office. He went underground after fruitlessly appealing his conviction, ultimately was captured by the FBI in 1970 and served 18 months in federal prison.

In 1980, he and his brother Philip became part of the Plowshares 8, a group that entered a General Electric facility in Pennsylvania, where they threw their own blood on unarmed nuclear weaponry. He was convicted, but the sentence was overturned.

Speaking at the convocation that opened Saint Rose’s academic year, Berrigan at first referred not to himself, but his brothers, Jerome, an English professor, and Philip, a former Josephite priest. Philip, 76, was sentenced in March to 30 months in prison for vandalizing aircraft at the Maryland Air National Guard Base. In 1982, Jerome served time for sprinkling blood at the Pentagon.

Both, he said, broke the taboos of the priesthood and academia. Neither priest nor professor is supposed to so publicly object to war. But Jerome, through literature, could not “push the illusion that all was well with the world.” And Christianity cannot be considered “as though a life of faith made no demands,” Berrigan said.

In his travels to colleges, Berrigan feels he has found little relief from military presence. “On each of these campuses, the military pedals its wares and offers scholarships.” He has tried to tweak the conscience of college administrators, angering one who cultivated a relationship with General Dynamics, maker of the Trident nuclear submarine, and shunning another who officiously refused a debate Berrigan had proposed about the military.

Berrigan sees greater hope for today’s students. Witness, he said, the turnout of students at a protest last fall at the Army’s School of the Americas, accused by its critics of training soldiers involved in civilian murders in Latin America.

“It seems to me that we have a lot of concerned students. The campuses are getting very lively again. The message is out about official violence and injustice. If we give the message truthfully and courageously, they get it.”

In fact, Berrigan’s invitation to a campus founded 80 years ago by The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet fits with this year’s theme of social justice, factored into lectures, special events and class projects, Saint Rose administrators said.

They did not know what Berrigan would say; Saint Rose, for instance, does not have an ROTC program, but if it did, officials would have had to answer Berrigan’s criticism of its presence on campuses.

“I think you would have to be naive that the prophets of our time, like the prophets of old, would not make us uncomfortable,” said the Rev. Christopher DeGiovine, dean of spiritual life. Berrigan is a “good catalyst” for colleges to provide a forum to ask tough questions and discuss ideas, said William J. Lowe, vice president for academic affairs.

Berrigan lately has turned to Biblical study to find answers to the difficulties of contemporary life. The result was a recent series of books on Old Testament prophets. “I wasn’t getting a lot of clear messages from my own church about human life, so I had to dig deeper.”

The conscience of the church needs balance, he said, describing it as tilting heavily toward opposing abortion yet belatedly objecting to war and capital punishment, for example.

His relationship with the church today is quieter than in the 1960s, when, he wrote in his autobiography, he was ostracized.

“Other Jesuits, and other people, have taken up the cause of peace,” said Berrigan, now living in a New York Jesuit community.

Berrigan, too, was present at the early scourge of AIDS, volunteering at a hospital in the West Village in New York. The work fit his lifelong theme.

“The whole question is one of human suffering and how we can alleviate it, and make it less likely that decent, good people have to die, or whomever. I was also testing myself.

“In dealing with the dying, I had to confront my own death. If I could walk with them, I could walk into my own future.”

#

Comments posted on this site are held in moderation until approved by a site administrator. Vulgar, profane, obscene, offensive terms or personal attacks will not be tolerated.