Just three years out of college, Katie Daddario DiCaprio ’02 helped develop the vaccine that now represents perhaps the best hope of slowing the spread of Ebola.

DiCaprio was a graduate student when she worked in the highly restricted military lab where day after day monkeys given the vaccine remained alert and healthy, following numerous failures. She co-authored a paper on the breakthrough that appeared in top journals and looked forward to working with her team to get the vaccine to market.

Now, a decade later, the National Institutes of Health has fast-tracked testing the Ebola vaccine but DiCaprio has mixed reactions. Had such steps been taken when it was developed in 2005, she notes, the epidemic in West Africa might have been contained. But there was no epidemic. Cases were almost non-existent and pharmaceutical companies were reluctant to spend millions of dollars on prevention. The vaccine was shelved.

“It’s tough to be proud when over 5,000 people have lost their lives,” says the Schenectady native, now 34, who devoted her Ph.D. dissertation to the vaccine. “I don’t have the expertise to say the epidemic could have been prevented. But maybe we could have saved lives. At least we’d know a lot more about the virus and the vaccine.”

In addition to researching treatments for Ebola and other infectious diseases, DiCaprio served as director of emergency preparedness and response for the New York City Department of Health’s Public Health Laboratory, during the H1N1 scare. She has now left bench-research for higher education, serving as chair and associate professor of health sciences at the College of Graduate Health Studies at A.T. Still University and as assistant professor of medical microbiology and immunology at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine.

She is no longer involved in Ebola research and has turned down most press interview requests. But based on the animal studies she took part in, she has high hopes for the vaccine, which had 100 percent success in the primates in her study.

“I would take it,” she said, from her office in New York City. “And I am confident of the results we saw in non-human primates. But only data from clinical trials will tell if it is safe in humans.”

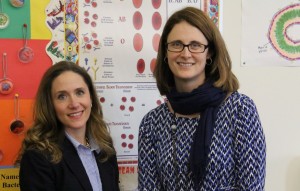

Now they are peers: Kate DiCaprio recently visited with a mentor, Kari Murad, a professor of biology who, like other members of the Saint Rose science faculty, was instrumental in guiding DiCaprio to pursue a career in fighting infectious diseases.

Katie Daddario was a serious student at Notre Dame-Bishop Gibbons High School who had been fascinated with infectious germs since childhood. She applied to Saint Rose because it was near home and offered rigorous academics. Working closely with professors in biology and chemistry, Kari Murad, Ann Zeeh, Steve Strazza and Sister Tess Wysolmerski, she fell in love with the natural sciences and became a biochemistry major. On the recommendation of Murad, an Albany Medical College graduate, DiCaprio spent a summer working in a lab there.

By graduation, she was more interested in seeking cures to disease than in treating patients. She had also learned how to reach for what she wanted.

“I’ll be honest. I’m not a prodigy,” noted DiCaprio, who retains strong ties to the College. “I got lucky and met some amazing people along the way who encouraged me. Now I tell my students ‘if you want to do something you really need to put yourself out there.’ It started at Saint Rose. They pushed me forward.”

Her fiancé, now husband, was in the Army and urged her to apply to the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the military’s medical school, which is based in Bethesda, Md. The school flew her there for an interview and accepted her the next day.

It was there that she saw Thomas Geisbert, a young, well-known Ebola researcher, give a presentation that changed her life.

“There were the most amazing images of disease,” DiCaprio recalled. “It painted a picture that made sense to me.” She introduced herself.

“He shook my hand and he didn’t let go at first,” she recalled. “Later he said it’s because I have small, strong hands. He said right away that I would be the ideal person for his lab.”

As a graduate assistant and later an employee, DiCaprio was the youngest, least-credentialed researcher in Geisbert’s level four (most restrictive) lab at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases. The atmosphere closely resembled what such labs look like in television dramas, where people in space suits handle the deadliest organisms on the planet.

It wasn’t just the biology and chemistry: DiCaprio, on a recent visit, said that at Saint Rose she was taught to reach for what she wanted – a lesson that has made all the difference in her career.

“It’s not just science, it’s your life,” she explained. “When you work in the BSL-4 in a positive pressure suit, you need to think ‘how do I pick this up, how do I hold this? If you drop something you have to bend down slowly and work with the airflow in your suit. If not, you could compromise its integrity. And you have to trust your life to the other people in the lab.”

Her group collaborated on Ebola with Health Canada, the agency that manages national healthcare in that country. To be successful, the vaccine needed to trigger a protective immune response to either neutralize the Ebola virus or keep it at a low level so the body’s own immune response could fight off infection. Many attempts had failed.

This time, a fraction of an Ebola gene was combined with VSV, a virus the team hoped triggered a response because it is not common. With previous attempts the primates became infected in only a few days and would soon die.

“This time, we drew the blood on day four and there was no change and we were getting excited, but we knew the game was not over,” she recalled. “By the time we hit day 10 we were really excited.”

The monkeys survived. The researchers published their findings in the top journal Nature Medicine. DiCaprio joined the team in an article and photo that ran on the front page of the Washington Post.

“I was only 24 years old,” she said. “I was a second-year graduate student and I had a publication in a top journal and more on the way.”

Her mentors let her know that she should prepare for the eventuality that more publications might not follow for a while, or ever. And indeed, the momentum slowed.

The team looked forward to moving the research to trials. But in spite of the wide publicity the discovery had drawn, it went no further. Geisbert was unable to get drug companies on board because Ebola was rare.

“It was discouraging,” she noted. “I came to Saint Rose because I wanted to make a difference and here we had perfect results we couldn’t get it past the lab.”

In October, the NIH, citing the urgency of protecting people against Ebola, began an early phase trial of the VSV Ebola vaccine. Geisbert, who is back in the news as a result, has said that he is not angry the vaccine was originally shelved, given the small incidence of Ebola at the time of its discovery. As for his young protégé?

DiCaprio concedes that the experience gave her pause. She is troubled that there was a possible solution that could not be used when it was needed. However, she has come to see that marketplace realities, along with science, are part of the equation.

“Right now I just hope the outbreak is contained soon and more help and resources are brought to the people in need,” she said. “And maybe this outbreak and the events surrounding it will serve as motivation for another young undergrad to want to make a difference.”

Comments posted on this site are held in moderation until approved by a site administrator. Vulgar, profane, obscene, offensive terms or personal attacks will not be tolerated.